Siemens' theory seems to rest upon two major conceits - the importance and validity of Buckminster Fuller's "knowledge-doubling curve," and the anticipated negative impact of technological determinism on society. Connectivism could be, in fact, viewed as Siemens' direct response to these two concerns. But are his concerns well-founded? And, if so, is his approach an effective solution to these issues?

In his book, Critical Path (1982), Fuller describes how prior to the 20th century, human knowledge doubled at the rate of about once every century. He called this the "knowledge-doubling curve" and that rate, according to Fuller, has been increasing exponentially throughout the 20th century. By 1999, it was estimated that human knowledge was doubling every 13 months, and some futurists predicted by the year 2020 the doubling-rate would occur every 12 hours. Siemens identifies this as a unique threat posed by the digital age and its new technologies, which, therefore, requires a novel solution. Is he right? Are we in a unique time of change?

First, it is important to note that there is no hard data to support Fuller's assumptions. It's not clear how he established the median growth rate of human knowledge from antiquity to the present. Even the concept of "human knowledge" is a construct that lacks a precise definition much like "human nature." So it's not clear what we are measuring. Is it the amount of declarative and procedural knowledge an individual is capable of easily accessing from their long-term memory? Is that even a concern?

Individual knowledge has almost always been a variable subset of "all that is known." Technology was employed centuries ago to offload the sum of everything we have learned in the form of books, which were collected in libraries - the analog to our modern databases. Long gone are the days of the Shen Kuos, Omar Khayyams, Leonardo da Vincis, Gottfried Leibnizs and the rest of the polymaths of lore (but even they used books).

This lack of clarity is extended into Siemens' characterization of learning and knowledge, which is critical to how he differentiates his theory from previous theories. He posits that learning is "no longer an internal, individualistic activity," which, for Siemens, is the hallmark of all other learning theories like behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism. But at its most fundamental, learning is an internal, biological process that is continuous. You can no more stop learning as you can stop hearing. Evolution has prioritized the mechanisms of learning as being too important for conscious control. Sensation, evaluation, judgement, and action are interrelated processes that are too critical to our survival to turn off.

The only mechanism that we are allowed some control over is our attention. We can seek out and choose to focus on experiences that interest us or that we determine require our attention (like mandatory corporate training), but we are always primed to learn. Those mechanisms are fairly invariant, and the idea that we can change the way we learn can be heaped upon the growing pile of neuromyths that pervade our profession. And while learning can take place at many levels, conscious and nonconscious, there is not a complete model of human cognition to-date, so I find Siemens' declaration of what learning is to be wholly unconvincing.

Otherwise, I agree with his focus on the importance of networked and social learning, which tracks closely to Leo Vygotsky's social constructivism so much so that, without the 'digital age' façade, it is nearly indistinguishable.

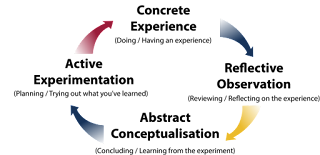

I think that David Kolb defined learning most accurately and succinctly in his paper describing his experiential learning theory. "Learning is the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience" (Kolb, pg. 38). As a learning design approach, I find that Kolb's focus on how information is encoded as knowledge through his Experiential Learning Cycle to be much more useful and less abstract than the recycled ideas embedded in connectivism.Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology & Distance Learning, 2, 3-10.

Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. FT press.

Comments

Post a Comment